Have you ever had a day where you blink and the sun is up? You take a few breaths. You turn around, and noon’s sun blazes down. Then somehow, as if no time has passed at all, twilight surrounds you. Darkness falls. And the day, which had only begun, has slipped past.

Time is a complex element within Baba Yaga’s stories, yet even the first time I heard of her horsemen—the horsemen in red, who brings the dawn; the horseman in white, who brings the brightness of daytime; and the horseman in black who brings the night—they felt familiar. Not only are there echoes of other mythologies in their travels, but some days can be like that, can’t they? Weeks and years can rush by. Time flies, not only when you’re having fun but when life keeps you on your toes.

These are no twelve horsemen of the apocalypse. They are Baba Yaga’s horsemen, controllers of time. Yes, the power in this ancient woman’s hand is so much greater than other cannibalistic witches you might know.

Oral traditions are harder to capture than a slip of the tongue, and characters like Baba Yaga don’t lend any simplicity to the hunt. Just as we forget that those around us do not see the intentions of our minds and hearts but only our words and actions, Baba Yaga too is a creation of others’ impressions. We don’t necessarily know her motivations, and that missing element adds to her enigma.

In our own lives, every day, our hearts strike out for the good of the world—or at least the good of our personal worlds in whatever way we can pursue it. Baba Yaga started in the same way. Earth goddess. Goddess of fertility. Goddess of the harvest. Force of regeneration. Caretaker of our ancestors’ wisdom. Gatekeeper between life and death, guiding souls through their birthing and dying. Yes, these are a part of her legacy too. Yet time, social movements, and politics do their damage.

Don’t we all know it? Though not all of us are recast as crones, as ogre witches, as monsters. At least not on our better days.

However, in true Baba Yaga style, she’s a babushka (grandmother) who owns her complexities and thrives in them. That’s a lesson for all of us. We see your assumptions, world, and here’s what we have to say about it. Or not. Actions should speak louder than words, but what if those actions are sometimes compassionate and sometimes malicious? Therein lies the rub.

Baba Yaga’s identity drifts one direction then another between places and times, but by traveling back into history and crossing her many inhabited lands, we can gather a better understanding of who she may have been, at least to some tellers of her tales.

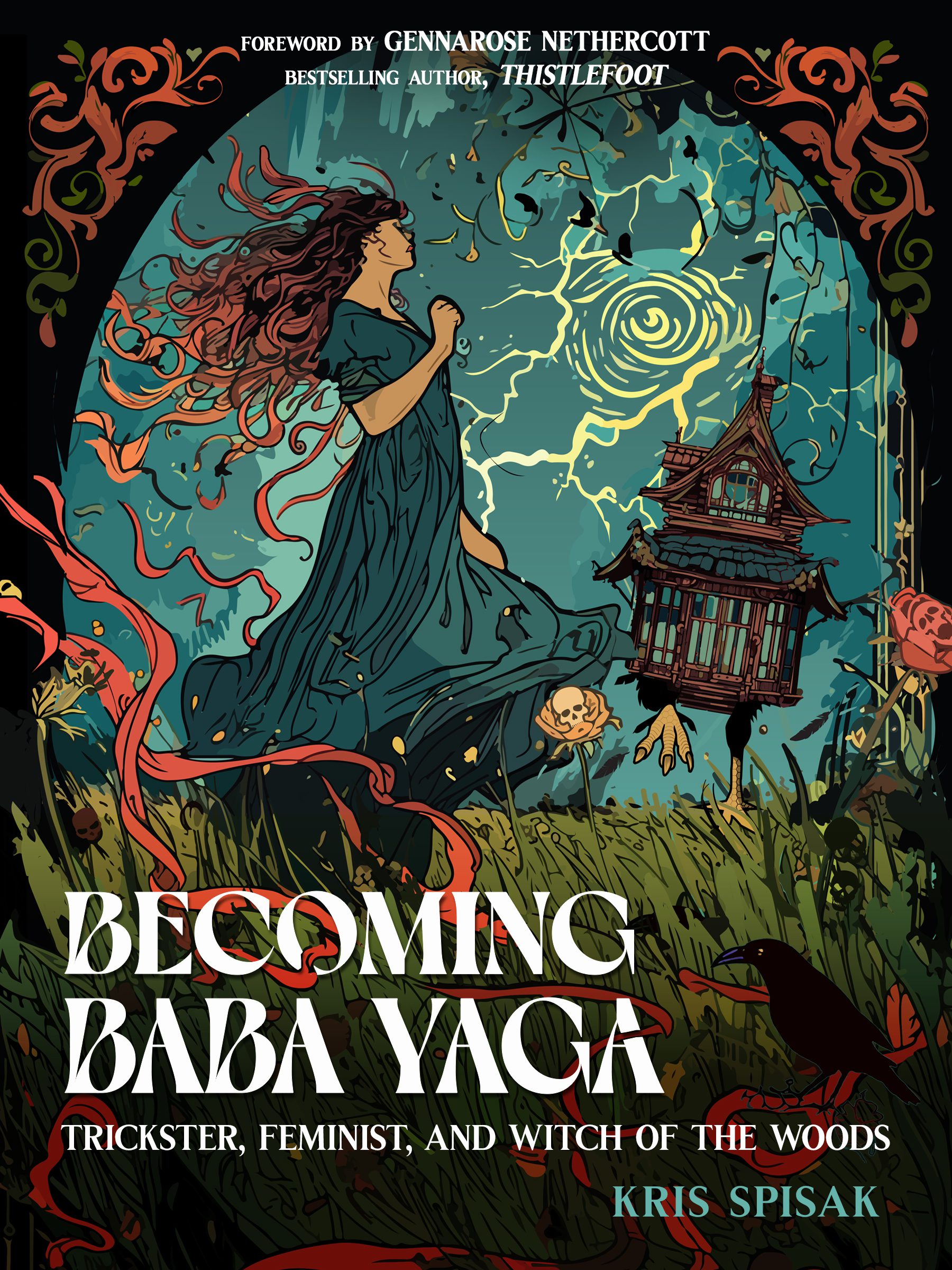

In contemporary popular culture, her name and character appear more frequently than we realize. The code name of Keanu Reeves’s titular character in the John Wick series is “Baba Yaga” within the dark organization where he operates. Hellboy comics and Dreamworks’ Puss in Boots introduce her as a character. Malware has been named after her, and the literary scene has certainly embraced her many possibilities. My own novel, The Baba Yaga Mask, is only one of a long legacy, including Orson Scott Card’s Enchantment and Diana Wynne Jones’s Howl’s Moving Castle with its parallel to a certain someone’s chicken-legged hut. While perhaps unfamiliar to American audiences at first glance, Baba Yaga’s presence is increasingly relevant to Western lives.

By trailing her backward through time, not only can we discover how she’s been introduced to prior generations; we can also pick up the clues of her origins and countless backstories. Specific episodes of our own lives shape and define us, and the same can be said for a folktale character who has existed in popular culture for hundreds of years, with her roots stretching into past millennia. Storytelling over such time spans is almost inconceivable, but our quest is a noble one—no matter how tangled in linguistic vines and hypothesis-laden thistle.

In a 1979 hand-drawn cartoon created by a Soviet-owned film studio, Baba Yaga and her accomplices tried to block the Olympic mascot, Misha the Bear, from playing in the Games. Released ahead of the 1980 Olympics, the old troublesome witch interfered as much as possible in this twenty-six-minute cartoon, even attempting to become the mascot herself, before entering the competition and comically failing repeatedly. Because the Moscow Olympics were boycotted by sixty-six countries, led by the United States, Baba Yaga’s role as interfering nuisance is considered a metaphor for the moment, her bumbling, destructive behaviors a parallel to Soviet impressions of the U.S.

Once again, she’s more complex than her face value, as grotesque—or as comical in this instance—as that face may be.

Of course, Baba Yaga was a common figure in Soviet-era cartoons from 1930s onward, often serving the morality tale trope to her child audiences. Be good and follow the rules of a well-organized society or else Baba Yaga will eat you! Big bad wolves and boogeymen historically have their roles, no matter your opinion on child-rearing or nationalistic propaganda.

Baba Yaga was known by the Czech version of her name, Ježibaba, in Antonin Dvořak’s opera Rusalka, which was first performed in Prague in 1901. While the storyline skews close to Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, Baba Yaga (as Ježibaba) has one of the best-known witch arias in operatic history, luring in the listener as she offers aid true to her dark forest roots.

Her legacy is as gnarled as the tree’ branches that surround her dark forest home, and we love her all the more for it.

Close to the same time as Dvořak’s opera, Anatoly Konstantinovich Lyadov composed a three-and-a-half-minute orchestral poem “Baba- Yaga” in 1904, following the tradition of Modest Mussorgsky’s 1874 orchestral arrangement “Pictures at an Exhibition.” The work of Victor Hartmann, an artist active amid the 1860s movement to revive Slavic folk songs, folktales, and traditions of medieval Russia, inspired Mussorgsky’s piece. Specifically, one of Hartmann’s watercolor pieces on display at the Academy of Fine Arts in Saint Petersburg in 1874, depicted a 14th-century style clock inspired by Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged hut. In turn, Mussorgsky’s ninth movement in “Pictures at an Exhibition” was titled “The Hut on Hen’s Legs.”

The Telephone game continues. Art begets art begets art, and I imagine Baba Yaga cackling all the while—whether hovering around creative circles, the audiences that consistently whisper and shrink back from her fame, or the shadowy forests and hidden alleyways of old villages where we might expect to find her.

Yet traveling back one hundred or one hundred fifty years is not really so far, when we know how long Baba Yaga has graced imaginations.

If we step back into the era of the birth of folktale studies, we may well come to know the work of Aleksandr Nikolayevich Afanasev. In his lifetime, Afanasev published nearly six hundred Slavic folktales and fairytales, from the first collection of seventy-four stories in 1855 to a significantly larger tome completed in 1863. Much like the Brothers Grimm, his roots were in academia. History, romanticism, mythology, and nature studies initially piqued his interest, with characters like Baba Yaga and Koscheii the Deathless biding their time in the inkless shadows, waiting for the moment their tales would flow from Afanasev’s pen.

Keep Koscheii in mind. Not only will we return to him, but he also was one of Baba Yaga’s accomplices during her brief animated stint at the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games.

Meanwhile, Afanasev was unique amid his folktale collecting contemporaries. He didn’t merely gather oral tales, changing them to his fancy. He collected versions of the tales, meticulously noting his sources, an invaluable record.

Afanasev was hardly the first of the Slavic fairytale collectors. He had multiple contemporaries, tracing back to the work of Vasilii Levshin, who is considered the first to capture Baba Yaga stories in writing. And we cannot ignore the 1788 comedic opera, Baba Yaga, by Prince Dmitry Gorchakov and Mathias Stabingher. Designed for Catherine the Great’s royal court, the ancient witch’s complex portrayal on stage makes me long to see this performance as it once was. Before the final curtain, Baba Yaga remains the sole character in the spotlight. Was she hunched, clenching a giant pestle? Was she dressed in rags or a gown as black as the dark forests of Russia? So many details are lost to history, even as we do know Baba Yaga closed the show with a solo about a better world that could come to be.

Terror. Hideousness. Hope. Possibility.

Yes, this is Baba Yaga, the witch, the motivational sorceress, sharing a lesson and a hint of optimism for audiences to take home. Members of Catherine the Great’s royal court, academics digging into dusty record books, modern readers who’ve always sensed a shadow aching to step into the spotlight and be heard—this is a character crafted through the ages for you all.

But like someone journeying into the woods, weaving between peeling birch trunks and dew-tipped thorns reaching out to pierce us—we must seek her out still, bracing ourselves as best we can as the pursuit begins to test us. We must creep beyond the easily accessible written records of history and published creativity.

We must track her to places where the forest’s onyx shadows are no different from the raven-inspired hues of night, where owls call no matter the hour, reminding us not to approach with demands but with the respect such an ancient elder surely deserves.

In her earliest known written record, Mikhail W. Lomonosov’s 1755 Russian Grammar, Baba Yaga was noted in an academically designed table, where gods, goddesses, and other deities of the world were connected with notes on their geography. The ancient Slavic god Perun, for example, was related with the Roman god Jupiter. Yet in this first-known textual documentation, Baba Yaga stood unaccompanied, with no comparisons the world over. She might have won me over in this detail alone, but let’s pause here for a moment.

This Russian grammar book is the beginning of her written legacy, but she’s clearly known to the population that may have encountered her here. Her first known written record is hardly an introduction. She’s named among the pantheons of gods and goddesses, no insignificant reputation.

Earlier still, woodblock prints known as lubki, popular in the 1600s and 1700s, are our earliest known confirmed representations of her. These decorations, originally fashioned from the carve-able layer of wood under the bark of linden trees, hung in the households of those who could not afford more expensive icons. Commonly sold for only a kopek or two, these simple prints were inked with a mixture of soot and burnt sienna boiled in linseed oil. They decorated homes and told stories, even to those who could not read. Lubki captured biblical tales, historical events, and yes, folktale stories well-known and well-treasured.

According to this artistic record, Baba Yaga was already a familiar character in this time period as well, able to stand on her own pictorially and be clearly identifiable. Imagining a cultural icon, a character captured in imaginations across Eastern Europe, but never written down in words is almost difficult for our modern minds to imagine. We live in an age of endless records, of content creation, and of mass media around every corner—corners both shadowy and well-lit in the sunshine. However, we must remember that literacy was not always as widespread as in the contemporary West. Oral traditions have a more extensive history. While harder to trace, these legacies hold equal value to messages preserved in parchment and ink, in chisel and stone. Stories are stories. They hold secrets, mysteries, and tremors of humanity within.

After all of the written and pictorial evidence, we can see how Baba Yaga was a familiar presence in the lives and memories of Slavic people across the regions of present-day Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Slovakia, Belarus, and beyond.

Was she connected with the Siberian bird goddess, known as a midwife? Her beak-like nose and her hut’s chicken legs may pay their own subtle homage.

Was she linked with another ancient Slavic goddess, tied to the underworld and known to be seated in an iron mortar like a throne, iron pestle in her hands? These objects didn’t grant her flight, but, oh, the relationship is far too palpable to ignore.

Do her roots lie in tales of Jezibaba, associated not with the collection of children’s bones after eating them but with the collection of baby teeth? Childhood traditions certainly spark their own tales.

Or should we examine the connection with the ancient being that carried the wisdom of time? She was believed to partner with Death as souls transitioned to the opposite side. Sure, “partner with death” sounds a touch macabre, but when wrapping our minds around the persona who guides souls as they enter life and as they leave it, this last role is among the most profound of all, no?

These goddesses, terrors, and traditions are all likely connections, fragments that rebuild and reshatter to create the disjointed and bewildering existence Baba Yaga has held in minds for centuries. Some scholars even trace Baba Yaga’s roots to the pre-Indo-European matrilinear pantheon, and logic exists in these foundations.

I don’t know about you, but I’m getting excited to roll up my sleeves and embark on this quest for an ogress witch who may also be a goddess.

Dusk begins to fall. Rustling leaves overhead beckon us into the forest’s obscurity. Scholars, academics, folklorists, and weavers of their own yarns link Baba Yaga to countless possibilities. The truth remains somewhere in the tangles of thorns and of threads. The headline can fearmonger to sell more subscriptions and to gain more clicks, but to grasp the entirety of the narrative, more time is required. Baba Yaga’s three horsemen should be able to help with that.

Examining ourselves, we know that who we are in any given minute of our lives is shaped by our past and present circumstances. All we have done and all the versions of ourselves we have been coalesce to refine us and define us. A folktale is no different. Baba Yaga’s stories exist and evolve, building upon their past derivations and seizing upon the new world, the unique societies that she discovers herself within.

No one folklorist, no one spiritualist, no one story captures Baba Yaga’s singular essence. Yet each leaves us clues to explore.

And so we shall.

Is her broom made of birch because birch trees are known as “the mother tree,” associated with fertility for centuries? Does this association arise from the tale of how birches were the first saplings that grew after the Ice Age, bringing life back after a frozen, desolate existence? Is it true? I don’t know, but wow is that a good story.

When examining folktales, we must always appreciate a narrative well-conceived. Only then do we let our curiosity push us on.

One of my favorite approaches to classic tales is in the tradition of the Ukrainian literary master, Lesya Ukrainka, who reimagined well-known tales with new parallels and purposes. In these pages, I mill Baba Yaga tales with a modern eye, as if I had a mortar and pestle of my own, grinding wheat berries down to bran and flour, crushing freshly picked herbs to release their oils and essence.

Recipes, medicines, and cocktails are known to transform with muddling. Stories do too.

And Baba Yaga has always embraced ongoing personal development.

She could be a goddess, a monster, or a little bit of both. Exploring all the remaining specks and nettles are a necessity, even if they may become stuck in our hair or a part of an old ogre witch’s brew. Curiosity is as much at the core of humanity as the desire for story itself, and where curiosity and story combine, you find the story historians whose fingers itch to turn back the pages to reveal more about who we have been, who we are, and what shadows and sparks linger to impact our collective future.

How did Baba Yaga become Baba Yaga, and what does the old woman still have to say to us? Let’s find out.

—Kris Spisak, Chapter 1, Clues to Explore, Copyright © 2024